Tuesday Poster Session

Category: Liver

P3880 - Under Disguise: A Concealed Case of Acute Hepatitis A Virus

Tuesday, October 24, 2023

10:30 AM - 4:00 PM PT

Location: Exhibit Hall

Has Audio

Kinan Obeidat, MD

University of Texas Medical Branch

Galveston, TX

Presenting Author(s)

Kinan Obeidat, MD1, Jordan Malone, DO1, Ernesto Zamora, MD1, Akshata Moghe, MD, PhD2

1University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX; 2UTMB, Galveston, TX

Introduction: Acute hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection is a vaccine-preventable viral infection stemming from fecal-oral transmission. Since 2016, HAV outbreaks have been publicly reported in 37 states totaling 44,864 cases of which 61% required hospitalization and 422 lead to death. While the diagnosis of acute HAV is typically elicited by a careful history and routine and serological blood work, the co-incidence of another acute illness can lead to a delay in diagnosis and subsequent proper management. Here, we present a case of acute HAV presenting concurrently with acute cholecystitis.

Case Description/Methods: A 36-year-old female with no significant past medical history presented with jaundice and mild, sporadic epigastric abdominal pain. Workup was significant for total bilirubin 13.5 mg/dL (direct 9 mg/dL), alkaline phosphatase 169 U/L, GGT 136 U/L, ALT 586 U/L, and AST 100 U/L. Ultrasound of the liver and gallbladder and a CT abdomen were significant for cholelithiasis with changes of acute cholecystitis. Given the hyperbilirubinemia, an ERCP was considered but MRCP did not reveal any biliary ductal dilation. The patient underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy with intraoperative cholangiography and liver biopsy. Intraoperative findings were consistent with acute cholecystitis without filling defects in the biliary tree. Concurrently, previously sent lab work returned positive for HAV IgM. Liver pathology showed acute viral hepatitis. Patient’s bilirubin continued to rise post-cholecystectomy, peaking at 21.8 mg/dL, lagging behind her AST and ALT which gradually down trended over a few days. Her symptoms improved, suggesting both relief from cholecystitis and resolution of acute HAV.

Discussion: Despite lab work suggestive of hepatocellular injury and severe hyperbilirubinemia with jaundice, the diagnosis of HAV was delayed due to the concurrent presentation of acute cholecystitis and lack of a typical prodrome for HAV infection. Our case highlights the fallacy of anchoring bias, wherein concurrent conditions are not considered because of complete reliance on the first piece of information received. Although the imaging diagnosis of cholecystitis was noted first, it is important to consider other possible diagnoses when the history and lab work do not completely fit the clinical picture. Though our patient was eventually accurately diagnosed and discharged without complication, missed or delayed diagnoses can be costly in patients who are elderly, immunocompromised, or with preexisting liver disease.

Disclosures:

Kinan Obeidat, MD1, Jordan Malone, DO1, Ernesto Zamora, MD1, Akshata Moghe, MD, PhD2. P3880 - Under Disguise: A Concealed Case of Acute Hepatitis A Virus, ACG 2023 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Vancouver, BC, Canada: American College of Gastroenterology.

1University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX; 2UTMB, Galveston, TX

Introduction: Acute hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection is a vaccine-preventable viral infection stemming from fecal-oral transmission. Since 2016, HAV outbreaks have been publicly reported in 37 states totaling 44,864 cases of which 61% required hospitalization and 422 lead to death. While the diagnosis of acute HAV is typically elicited by a careful history and routine and serological blood work, the co-incidence of another acute illness can lead to a delay in diagnosis and subsequent proper management. Here, we present a case of acute HAV presenting concurrently with acute cholecystitis.

Case Description/Methods: A 36-year-old female with no significant past medical history presented with jaundice and mild, sporadic epigastric abdominal pain. Workup was significant for total bilirubin 13.5 mg/dL (direct 9 mg/dL), alkaline phosphatase 169 U/L, GGT 136 U/L, ALT 586 U/L, and AST 100 U/L. Ultrasound of the liver and gallbladder and a CT abdomen were significant for cholelithiasis with changes of acute cholecystitis. Given the hyperbilirubinemia, an ERCP was considered but MRCP did not reveal any biliary ductal dilation. The patient underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy with intraoperative cholangiography and liver biopsy. Intraoperative findings were consistent with acute cholecystitis without filling defects in the biliary tree. Concurrently, previously sent lab work returned positive for HAV IgM. Liver pathology showed acute viral hepatitis. Patient’s bilirubin continued to rise post-cholecystectomy, peaking at 21.8 mg/dL, lagging behind her AST and ALT which gradually down trended over a few days. Her symptoms improved, suggesting both relief from cholecystitis and resolution of acute HAV.

Discussion: Despite lab work suggestive of hepatocellular injury and severe hyperbilirubinemia with jaundice, the diagnosis of HAV was delayed due to the concurrent presentation of acute cholecystitis and lack of a typical prodrome for HAV infection. Our case highlights the fallacy of anchoring bias, wherein concurrent conditions are not considered because of complete reliance on the first piece of information received. Although the imaging diagnosis of cholecystitis was noted first, it is important to consider other possible diagnoses when the history and lab work do not completely fit the clinical picture. Though our patient was eventually accurately diagnosed and discharged without complication, missed or delayed diagnoses can be costly in patients who are elderly, immunocompromised, or with preexisting liver disease.

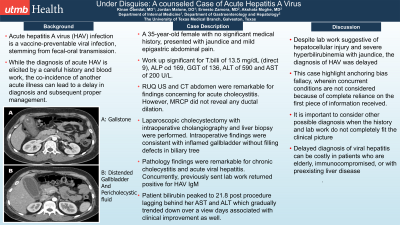

Figure: A: CT abdomen showing a stone in the gallbladder

B: CT abdomen showing signs consistent with acute cholecystitis

B: CT abdomen showing signs consistent with acute cholecystitis

Disclosures:

Kinan Obeidat indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Jordan Malone indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Ernesto Zamora indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Akshata Moghe indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Kinan Obeidat, MD1, Jordan Malone, DO1, Ernesto Zamora, MD1, Akshata Moghe, MD, PhD2. P3880 - Under Disguise: A Concealed Case of Acute Hepatitis A Virus, ACG 2023 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Vancouver, BC, Canada: American College of Gastroenterology.