Tuesday Poster Session

Category: General Endoscopy

P3410 - A Case Series: Rare Primary Melanomas of the Gastrointestinal Tract

Tuesday, October 24, 2023

10:30 AM - 4:00 PM PT

Location: Exhibit Hall

Has Audio

Sushreyta Rose, DO

University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio

San Antonio, TX

Presenting Author(s)

Sushreyta Rose, DO1, Jessica Basso, MD2, Grace Hopp, DO, MBA3, Brenda Briones, MD1, Juan Echavarria, MD1

1University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX; 2Brooke Army Medical Center, Fort Sam Houston, TX; 3UT Health San Antonio, San Antonio, TX

Introduction: Although rare compared to metastatic lesions from an oculocutaneous primary, primary gastrointestinal melanomas (PGIM), arising from the mucosa, have shown increasing incidence and poor survival. We present two cases of PGIM with different presentations and endoscopic appearances.

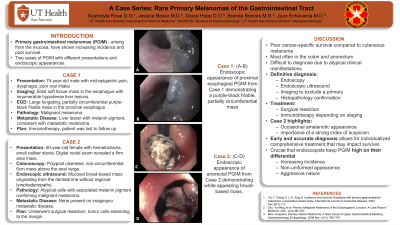

Case Description/Methods: Case 1: A 74-year-old male presented with mid-epigastric pain, dysphagia, and poor oral intake. Imaging revealed a solid soft tissue mass in the esophagus with innumerable hypodense liver lesions. Upper endoscopy revealed a large fungating, partially circumferential purple-black friable mass in the proximal esophagus. Biopsies demonstrated malignant melanoma. Core needle samples of a metastatic liver lesion showed malignant cells with melanin pigment, morphologically consistent with metastatic melanoma. Ophthalmologic and skin exam did not reveal a primary. Plan was to initiate immunotherapy, however patient was lost to follow up.

Case 2: A 50-year-old female presented with hematochezia and small caliber stools in clinic. Digital rectal exam revealed a firm anal mass. Colonoscopy showed a polypoid ulcerated, non-circumferential 6cm mass above the anal verge. Endoscopic ultrasound demonstrated a mucosal broad-based mass originating from the dentate line without regional lymphadenopathy. Biopsies showed atypical cells with associated melanin pigment confirming malignant melanoma. Imaging revealed no metastatic disease. Patient underwent surgical resection, with tumor cells extending to the margin.

Discussion: A review by Kahl et al. of 872 cases from 1973-2016 highlights the rarity and poor cancer-specific survival of PGIM compared to cutaneous melanoma. A population-based study by Du et al. demonstrated increased incidence, most often in the colon and anorectum. It is characterized by rapid progression and is difficult to diagnose due to atypical clinical manifestations. Definitive diagnosis requires endoscopy, endoscopic ultrasound, imaging to exclude a primary, and histopathology confirmation. Treatment includes surgical resection or immunotherapy depending on staging.

Our second case highlights the occasional amelanotic appearance which can be misleading to endoscopists and highlights the importance of a strong index of suspicion. Given the increasing incidence, non-uniformed appearance, and aggressive nature, it is crucial that endoscopists keep PGIM high on their differential. Early and accurate diagnosis allows for individualized comprehensive treatment that may impact survival.

Disclosures:

Sushreyta Rose, DO1, Jessica Basso, MD2, Grace Hopp, DO, MBA3, Brenda Briones, MD1, Juan Echavarria, MD1. P3410 - A Case Series: Rare Primary Melanomas of the Gastrointestinal Tract, ACG 2023 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Vancouver, BC, Canada: American College of Gastroenterology.

1University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX; 2Brooke Army Medical Center, Fort Sam Houston, TX; 3UT Health San Antonio, San Antonio, TX

Introduction: Although rare compared to metastatic lesions from an oculocutaneous primary, primary gastrointestinal melanomas (PGIM), arising from the mucosa, have shown increasing incidence and poor survival. We present two cases of PGIM with different presentations and endoscopic appearances.

Case Description/Methods: Case 1: A 74-year-old male presented with mid-epigastric pain, dysphagia, and poor oral intake. Imaging revealed a solid soft tissue mass in the esophagus with innumerable hypodense liver lesions. Upper endoscopy revealed a large fungating, partially circumferential purple-black friable mass in the proximal esophagus. Biopsies demonstrated malignant melanoma. Core needle samples of a metastatic liver lesion showed malignant cells with melanin pigment, morphologically consistent with metastatic melanoma. Ophthalmologic and skin exam did not reveal a primary. Plan was to initiate immunotherapy, however patient was lost to follow up.

Case 2: A 50-year-old female presented with hematochezia and small caliber stools in clinic. Digital rectal exam revealed a firm anal mass. Colonoscopy showed a polypoid ulcerated, non-circumferential 6cm mass above the anal verge. Endoscopic ultrasound demonstrated a mucosal broad-based mass originating from the dentate line without regional lymphadenopathy. Biopsies showed atypical cells with associated melanin pigment confirming malignant melanoma. Imaging revealed no metastatic disease. Patient underwent surgical resection, with tumor cells extending to the margin.

Discussion: A review by Kahl et al. of 872 cases from 1973-2016 highlights the rarity and poor cancer-specific survival of PGIM compared to cutaneous melanoma. A population-based study by Du et al. demonstrated increased incidence, most often in the colon and anorectum. It is characterized by rapid progression and is difficult to diagnose due to atypical clinical manifestations. Definitive diagnosis requires endoscopy, endoscopic ultrasound, imaging to exclude a primary, and histopathology confirmation. Treatment includes surgical resection or immunotherapy depending on staging.

Our second case highlights the occasional amelanotic appearance which can be misleading to endoscopists and highlights the importance of a strong index of suspicion. Given the increasing incidence, non-uniformed appearance, and aggressive nature, it is crucial that endoscopists keep PGIM high on their differential. Early and accurate diagnosis allows for individualized comprehensive treatment that may impact survival.

Figure: Figure 1 (A-D): Endoscopic appearances of PGIM from Case 1 and Case 2. (A-B) Endoscopic appearance of proximal esophageal PGIM from Case 1 demonstrating a purple-black friable, partially circumferential mass; (C-D) Endoscopic appearance of anorectal PGIM from Case 2 demonstrating white appearing broad-based mass.

Disclosures:

Sushreyta Rose indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Jessica Basso indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Grace Hopp indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Brenda Briones indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Juan Echavarria indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Sushreyta Rose, DO1, Jessica Basso, MD2, Grace Hopp, DO, MBA3, Brenda Briones, MD1, Juan Echavarria, MD1. P3410 - A Case Series: Rare Primary Melanomas of the Gastrointestinal Tract, ACG 2023 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Vancouver, BC, Canada: American College of Gastroenterology.