Sunday Poster Session

Category: Esophagus

P0442 - Acquired Tracheoesophageal Fistula

Sunday, October 22, 2023

3:30 PM - 7:00 PM PT

Location: Exhibit Hall

Has Audio

Kyle Marrache, DO

Abington Jefferson Hospital

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Presenting Author(s)

Kyle Marrache, DO1, Shravya Ginnaram, MD2, Sarah Elrod, DO2, Stephanie Tzarnas, MD3, Tessa Connelly, MD4

1Abington Jefferson Hospital, Philadelphia, PA; 2Jefferson Abington Hospital, Abington, PA; 3Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia, PA; 4Abington Jefferson Health, Philadelphia, PA

Introduction: Tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF) can be either congenital or acquired with the latter being much rarer. With respect to acquired TEF the two major types are malignant and benign. Numerous causes of benign TEF exist but the major risk factor is mechanical ventilation. We present a case of acquired TEF due to mechanical ventilation which went undiagnosed for a significant amount of time and caused numerous respiratory infections before being discovered.

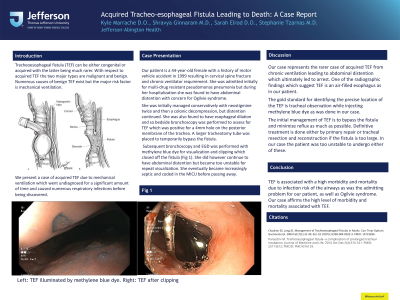

Case Description/Methods: Our patient is a 44-year-old female with a history of motor vehicle accident in 1999 resulting in cervical spine fracture and chronic ventilator requirement. She was admitted initially for multi-drug resistant pseudomonas pneumonia but during her hospitalization she was found to have abdominal distention with concern for Ogilvie syndrome. She was initially managed conservatively with neostigmine twice and then a colonic decompression, but distention continued. She was also found to have esophageal dilation and so bedside bronchoscopy was performed to assess for TEF which was positive for a 4mm hole on the posterior membrane of the trachea. A larger tracheotomy tube was placed to temporarily bypass the fistula. Subsequent bronchoscopy and EGD was performed with methylene blue dye for visualization and clipping which closed off the fistula (Fig 1). She did however continue to have abdominal distention but became too unstable for repeat visualization. She eventually became increasingly septic and coded in the MICU before passing away.

Discussion: Our case represents the rarer case of acquired TEF from chronic ventilation leading to abdominal distention which ultimately led to arrest. One of the radiographic findings which suggest TEF is an air-filled esophagus as in our patient. The gold standard for identifying the precise location of the TEF is tracheal observation while injecting methylene blue dye as was done in our case. The initial management of TEF is to bypass the fistula and minimize reflux as much as possible. Definitive treatment is done either by primary repair or tracheal resection and reconstruction if the fistula is too large. In our case the patient was too unstable to undergo either of these.

TEF is associated with a high morbidity and mortality due to infection risk of the airways as was the admitting problem for our patient, as well as Ogilvie syndrome. Our case affirms the high level of morbidity and mortality associated with TEF.

Disclosures:

Kyle Marrache, DO1, Shravya Ginnaram, MD2, Sarah Elrod, DO2, Stephanie Tzarnas, MD3, Tessa Connelly, MD4. P0442 - Acquired Tracheoesophageal Fistula, ACG 2023 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Vancouver, BC, Canada: American College of Gastroenterology.

1Abington Jefferson Hospital, Philadelphia, PA; 2Jefferson Abington Hospital, Abington, PA; 3Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia, PA; 4Abington Jefferson Health, Philadelphia, PA

Introduction: Tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF) can be either congenital or acquired with the latter being much rarer. With respect to acquired TEF the two major types are malignant and benign. Numerous causes of benign TEF exist but the major risk factor is mechanical ventilation. We present a case of acquired TEF due to mechanical ventilation which went undiagnosed for a significant amount of time and caused numerous respiratory infections before being discovered.

Case Description/Methods: Our patient is a 44-year-old female with a history of motor vehicle accident in 1999 resulting in cervical spine fracture and chronic ventilator requirement. She was admitted initially for multi-drug resistant pseudomonas pneumonia but during her hospitalization she was found to have abdominal distention with concern for Ogilvie syndrome. She was initially managed conservatively with neostigmine twice and then a colonic decompression, but distention continued. She was also found to have esophageal dilation and so bedside bronchoscopy was performed to assess for TEF which was positive for a 4mm hole on the posterior membrane of the trachea. A larger tracheotomy tube was placed to temporarily bypass the fistula. Subsequent bronchoscopy and EGD was performed with methylene blue dye for visualization and clipping which closed off the fistula (Fig 1). She did however continue to have abdominal distention but became too unstable for repeat visualization. She eventually became increasingly septic and coded in the MICU before passing away.

Discussion: Our case represents the rarer case of acquired TEF from chronic ventilation leading to abdominal distention which ultimately led to arrest. One of the radiographic findings which suggest TEF is an air-filled esophagus as in our patient. The gold standard for identifying the precise location of the TEF is tracheal observation while injecting methylene blue dye as was done in our case. The initial management of TEF is to bypass the fistula and minimize reflux as much as possible. Definitive treatment is done either by primary repair or tracheal resection and reconstruction if the fistula is too large. In our case the patient was too unstable to undergo either of these.

TEF is associated with a high morbidity and mortality due to infection risk of the airways as was the admitting problem for our patient, as well as Ogilvie syndrome. Our case affirms the high level of morbidity and mortality associated with TEF.

Figure: Tracheoesophageal Fistula shown with dye on left. Clips in place after closure on the right.

Disclosures:

Kyle Marrache indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Shravya Ginnaram indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Sarah Elrod indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Stephanie Tzarnas indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Tessa Connelly indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Kyle Marrache, DO1, Shravya Ginnaram, MD2, Sarah Elrod, DO2, Stephanie Tzarnas, MD3, Tessa Connelly, MD4. P0442 - Acquired Tracheoesophageal Fistula, ACG 2023 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Vancouver, BC, Canada: American College of Gastroenterology.