Monday Poster Session

Category: GI Bleeding

P2081 - A Case of Downhill Esophageal Varices Secondary to Prior Hemodialysis Catheter Placement

Monday, October 23, 2023

10:30 AM - 4:15 PM PT

Location: Exhibit Hall

Has Audio

- CP

Colton J. Pence, BS, MD

New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center

New York, NY

Presenting Author(s)

Colton J. Pence, BS, MD1, Vladislav Fomin, MD2, Lasha Gogokhia, MD3, Robert Schwartz, MD, PhD1, Dana Lukin, MD, PhD, FACG4, David Wan, BS, MD5

1New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York, NY; 2New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY; 3New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York, NY; 4Jill Roberts Center for Inflammatory Bowel Disease, New York, NY; 5Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, NY

Introduction: Esophageal varices are a life-threatening condition that is most commonly secondary to cirrhosis and other liver disease. Downhill esophageal varices can occur secondary to superior vena cava (SVC) obstruction and are a rare cause of non-portal hypertension gastrointestinal bleeding. Downhill esophageal varices are most commonly associated with SVC obstruction secondary to prior venous dialysis catheter placement in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD). This case will discuss a patient with ESRD who was found to have downhill esophageal varices.

Case Description/Methods: A 34-year-old man with ESRD on peritoneal dialysis with a longstanding history of prior hemodialysis presented with acute abdominal pain. Imaging demonstrated acute appendicitis, and laparoscopic appendectomy was performed. Postoperatively, the patient experienced several episodes of hematemesis with an acute drop in hemoglobin (9.4 to 6.8). Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed proximal varices without any stigmata of bleeding and grade D erosive esophagitis. These were suspicious for downhill varices given a history of chronic right brachiocephalic occlusion. Repeat EGD the next day showed esophagitis, a hiatal hernia and three columns of large ( >5mm) proximal varices. Vascular surgery did not recommend SCV stenting at this time. He was managed supportively and discharged. A week later he was readmitted with melena and critical anemia (hemoglobin 4.3). Repeat EGD showed proximal varices without stigmata of bleeding and a healing Cameron ulcer circumferentially. His bleeding source was suspected to be due to esophagitis and the Cameron ulcer. After stabilization he was discharged without evidence of active bleeding.

Discussion: Downhill varices occur due to collateralization from the SVC to the inferior vena cava and have a lower bleeding risk than uphill varices due to lower venous pressure gradients in the upper esophagus. There are currently no direct guidelines regarding management of downhill varices. Treatment focuses on managing the underlying cause of obstruction, such as with SVC stenting. There is a higher risk of complications, such as bleeding or perforation, with endoscopic treatment of downhill varices due to the location in the upper esophagus. However, in high risk patients or those with active hemorrhage, aggressive management such as band ligation or scleropathy may be required. Given this patient’s lack of active variceal bleeding or bleeding stigmata, conservative management was emphasized.

Disclosures:

Colton J. Pence, BS, MD1, Vladislav Fomin, MD2, Lasha Gogokhia, MD3, Robert Schwartz, MD, PhD1, Dana Lukin, MD, PhD, FACG4, David Wan, BS, MD5. P2081 - A Case of Downhill Esophageal Varices Secondary to Prior Hemodialysis Catheter Placement, ACG 2023 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Vancouver, BC, Canada: American College of Gastroenterology.

1New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York, NY; 2New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY; 3New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York, NY; 4Jill Roberts Center for Inflammatory Bowel Disease, New York, NY; 5Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, NY

Introduction: Esophageal varices are a life-threatening condition that is most commonly secondary to cirrhosis and other liver disease. Downhill esophageal varices can occur secondary to superior vena cava (SVC) obstruction and are a rare cause of non-portal hypertension gastrointestinal bleeding. Downhill esophageal varices are most commonly associated with SVC obstruction secondary to prior venous dialysis catheter placement in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD). This case will discuss a patient with ESRD who was found to have downhill esophageal varices.

Case Description/Methods: A 34-year-old man with ESRD on peritoneal dialysis with a longstanding history of prior hemodialysis presented with acute abdominal pain. Imaging demonstrated acute appendicitis, and laparoscopic appendectomy was performed. Postoperatively, the patient experienced several episodes of hematemesis with an acute drop in hemoglobin (9.4 to 6.8). Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed proximal varices without any stigmata of bleeding and grade D erosive esophagitis. These were suspicious for downhill varices given a history of chronic right brachiocephalic occlusion. Repeat EGD the next day showed esophagitis, a hiatal hernia and three columns of large ( >5mm) proximal varices. Vascular surgery did not recommend SCV stenting at this time. He was managed supportively and discharged. A week later he was readmitted with melena and critical anemia (hemoglobin 4.3). Repeat EGD showed proximal varices without stigmata of bleeding and a healing Cameron ulcer circumferentially. His bleeding source was suspected to be due to esophagitis and the Cameron ulcer. After stabilization he was discharged without evidence of active bleeding.

Discussion: Downhill varices occur due to collateralization from the SVC to the inferior vena cava and have a lower bleeding risk than uphill varices due to lower venous pressure gradients in the upper esophagus. There are currently no direct guidelines regarding management of downhill varices. Treatment focuses on managing the underlying cause of obstruction, such as with SVC stenting. There is a higher risk of complications, such as bleeding or perforation, with endoscopic treatment of downhill varices due to the location in the upper esophagus. However, in high risk patients or those with active hemorrhage, aggressive management such as band ligation or scleropathy may be required. Given this patient’s lack of active variceal bleeding or bleeding stigmata, conservative management was emphasized.

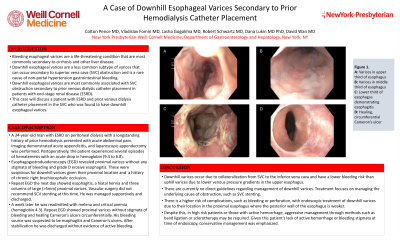

Figure: A) Esophageal varices in the upper third of the esophagus B) Esophageal varices in the middle third of the esophagus C) Esophagitis, grade D, in lower third of the esophagus D) Healing Cameron ulcer in lower third of esophagus

Disclosures:

Colton Pence indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Vladislav Fomin indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Lasha Gogokhia indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Robert Schwartz indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Dana Lukin: Abbvie – Advisory Committee/Board Member, Consultant, Grant/Research Support, Speakers Bureau. Boehringer Ingelheim – Consultant, Grant/Research Support. Bristol Myers Squibb – Advisory Committee/Board Member. Eli Lilly – Consultant. Fresenius Kabi – Consultant. Janssen – Advisory Committee/Board Member, Consultant, Grant/Research Support, Speakers Bureau. Magellan Health – Consultant. Palatin – Consultant. Pfizer – Consultant. Prometheus – Consultant. PSI – Consultant. Takeda – Consultant, Grant/Research Support.

David Wan indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Colton J. Pence, BS, MD1, Vladislav Fomin, MD2, Lasha Gogokhia, MD3, Robert Schwartz, MD, PhD1, Dana Lukin, MD, PhD, FACG4, David Wan, BS, MD5. P2081 - A Case of Downhill Esophageal Varices Secondary to Prior Hemodialysis Catheter Placement, ACG 2023 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Vancouver, BC, Canada: American College of Gastroenterology.