Monday Poster Session

Category: GI Bleeding

P2090 - Find That Bleed! A Case of Hemobilia Due to Cystic Artery Pseudoaneurysm in a Patient With Persistent Melena

Monday, October 23, 2023

10:30 AM - 4:15 PM PT

Location: Exhibit Hall

Has Audio

.jpg)

Kevin Edward E. Nebrejas, MD

University of Hawaii

Honolulu, HI

Presenting Author(s)

Kevin Edward Nebrejas, MD1, Arvin Tan, MD2, Daniel K. Chan, MD3, Traci T. Murakami, MD4

1University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI; 2University of Hawaii, John A. Burns School of Medicine, Honolulu, HI; 3Queen's Medical Center, Mililani, HI; 4Queen's Medical Center - West Oahu, Ewa Beach, HI

Introduction: Cystic Artery Pseudoaneurysm (CAP) is a rare cause of hemobilia. The incidence of hemobilia is 2-5% in upper gastrointestinal bleeding with cholecystectomy-related iatrogenic injury being the most common cause. A high index of suspicion for hemobilia should be considered in patients with cholecystitis and with otherwise unexplained GI hemorrhage.

Case Description/Methods: A 64-year-old male with atrial fibrillation and heart failure presented to the emergency department for melena. He was hospitalized one-week prior due to a similar episode at which point he was found to have a dieulafoy lesion in the transverse colon and CT angiography incidentally revealing cholecystitis, which was managed conservatively with amoxicillin/clavulanate for 7 days. During this visit, repeat CT angiography showed unremarkable findings hence a tagged RBC scan was done demonstrating active bleeding in the proximal to mid-ileum. EGD showed bleeding in the major papilla prompting further investigation. MRI of the liver showed a 2.1 x 1.8-cm mass in the gallbladder suggestive of malignancy. A mesenteric angiogram was performed revealing a cystic artery pseudoaneurysm. The patient was then started on octreotide and underwent laparoscopic robotic assisted cholecystectomy. He was noted to have a chronically inflamed gallbladder with the transverse colon affixed to the inferior liver edge. Vessel sealer was used for the cystic artery. Pathology of the gallbladder was consistent with acute and chronic cholecystitis with mural hemorrhage. Follow-up EGD and colonoscopy after 2 weeks showed resolution of bleeding. Of note, he required 16 units of packed RBC during hospitalization.

Discussion: Due to the rarity of this condition, no consensus guidelines exist for the diagnosis and treatment of visceral artery aneurysms. In this case, prior extensive work up failed to resolve GI bleeding. Mesenteric angiogram eventually elucidated the definitive diagnosis. Treatment with cholecystectomy was performed over coiling, which was deemed unsafe without compromising the right hepatic artery. Embolization was avoided due to risk of perforation, necrosis or sepsis. Given the critical nature of this condition, delayed or missed diagnosis can be fatal. It is important to recognize that standard imaging modalities such as endoscopy and ultrasound may fail to detect the source of bleeding. Thus, it is important to have a high index of suspicion and include visceral artery aneurysms in the differential for patients presenting with GI bleeding.

Disclosures:

Kevin Edward Nebrejas, MD1, Arvin Tan, MD2, Daniel K. Chan, MD3, Traci T. Murakami, MD4. P2090 - Find That Bleed! A Case of Hemobilia Due to Cystic Artery Pseudoaneurysm in a Patient With Persistent Melena, ACG 2023 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Vancouver, BC, Canada: American College of Gastroenterology.

1University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI; 2University of Hawaii, John A. Burns School of Medicine, Honolulu, HI; 3Queen's Medical Center, Mililani, HI; 4Queen's Medical Center - West Oahu, Ewa Beach, HI

Introduction: Cystic Artery Pseudoaneurysm (CAP) is a rare cause of hemobilia. The incidence of hemobilia is 2-5% in upper gastrointestinal bleeding with cholecystectomy-related iatrogenic injury being the most common cause. A high index of suspicion for hemobilia should be considered in patients with cholecystitis and with otherwise unexplained GI hemorrhage.

Case Description/Methods: A 64-year-old male with atrial fibrillation and heart failure presented to the emergency department for melena. He was hospitalized one-week prior due to a similar episode at which point he was found to have a dieulafoy lesion in the transverse colon and CT angiography incidentally revealing cholecystitis, which was managed conservatively with amoxicillin/clavulanate for 7 days. During this visit, repeat CT angiography showed unremarkable findings hence a tagged RBC scan was done demonstrating active bleeding in the proximal to mid-ileum. EGD showed bleeding in the major papilla prompting further investigation. MRI of the liver showed a 2.1 x 1.8-cm mass in the gallbladder suggestive of malignancy. A mesenteric angiogram was performed revealing a cystic artery pseudoaneurysm. The patient was then started on octreotide and underwent laparoscopic robotic assisted cholecystectomy. He was noted to have a chronically inflamed gallbladder with the transverse colon affixed to the inferior liver edge. Vessel sealer was used for the cystic artery. Pathology of the gallbladder was consistent with acute and chronic cholecystitis with mural hemorrhage. Follow-up EGD and colonoscopy after 2 weeks showed resolution of bleeding. Of note, he required 16 units of packed RBC during hospitalization.

Discussion: Due to the rarity of this condition, no consensus guidelines exist for the diagnosis and treatment of visceral artery aneurysms. In this case, prior extensive work up failed to resolve GI bleeding. Mesenteric angiogram eventually elucidated the definitive diagnosis. Treatment with cholecystectomy was performed over coiling, which was deemed unsafe without compromising the right hepatic artery. Embolization was avoided due to risk of perforation, necrosis or sepsis. Given the critical nature of this condition, delayed or missed diagnosis can be fatal. It is important to recognize that standard imaging modalities such as endoscopy and ultrasound may fail to detect the source of bleeding. Thus, it is important to have a high index of suspicion and include visceral artery aneurysms in the differential for patients presenting with GI bleeding.

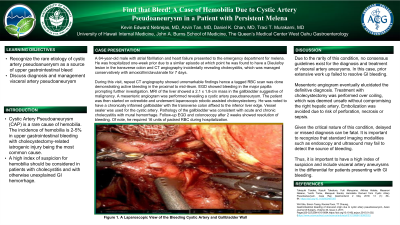

Figure: Laparoscopic view of the bleeding cystic artery and the gallbladder wall.

Disclosures:

Kevin Edward Nebrejas indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Arvin Tan indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Daniel Chan indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Traci Murakami indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Kevin Edward Nebrejas, MD1, Arvin Tan, MD2, Daniel K. Chan, MD3, Traci T. Murakami, MD4. P2090 - Find That Bleed! A Case of Hemobilia Due to Cystic Artery Pseudoaneurysm in a Patient With Persistent Melena, ACG 2023 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Vancouver, BC, Canada: American College of Gastroenterology.