Monday Poster Session

Category: Stomach

P2793 - A Case of Malignant Melanoma With Metastases to the Stomach

Monday, October 23, 2023

10:30 AM - 4:15 PM PT

Location: Exhibit Hall

Has Audio

Jacob M. Bauss, MD

Michigan State University College of Human Medicine

Rochester, MN

Presenting Author(s)

Jacob M. Bauss, MD1, Jason Puckett, MD2, Chelsea M. Styles, MD3

1Michigan State University College of Human Medicine, Grand Rapids, MI; 2Corewell Health, Byron Center, MI; 3Michigan Pathology Specialists/Corewell Health, Grand Rapids, MI

Introduction: The most common cancers that metastasize to the gastrointestinal (GI) tract are melanoma and breast cancer with the small intestine being the most common site followed by stomach, colon and esophagus. Due to the non-specific symptoms and variability of lesions on endoscopy, diagnosis of metastatic melanoma to the GI tract tends to be delayed. Prompt recognition is important to direct therapy and minimize potential complications.

Case Description/Methods: A 47-year-old male with a past medical history of asthma on 20 mg prednisone daily and metastatic melanoma to the brain, liver, and lungs on vemurafenib and cobimetinib presented to the hospital for two weeks of epigastric pain and melena. A non-contrast CT scan showed new abdominal adenopathy near the gastrohepatic ligament. He was mildly anemic with a hemoglobin of 12.7 g/dL (14-17.5 g/dL). Upper endoscopy revealed a large ulcerated friable mass in the gastric body. Biopsy showed atypical infiltrative cells in the gastric mucosa which were positive for SOX10, HMB-45, tyrosinase, and Melan-A (MART-1) confirming the diagnosis of metastatic melanoma. The patient was placed on twice daily 40 mg pantoprazole and continued on kinase inhibitor therapy with resolution of the melena and improvement in abdominal pain. He was discharged one day following the procedure with close follow-up by the gastroenterology and oncology team.

Discussion: Metastatic melanoma to the stomach is rare with the diagnosis being delayed due to non-specific symptoms. Prognosis is poor with an average life expectancy of 6 months. Endoscopic appearance of gastric melanoma varies greatly among cases necessitating the need for biopsy to confirm the diagnosis via histological identification and immunohistochemical staining. Differentiation of primary GI melanoma versus metastatic melanoma is also important to guide therapy and can be delineated by patient history and genetic markers. Dual kinase inhibitor therapy has shown improved progression-free survival and overall survival when used for unresectable metastatic melanoma, however, treatment resistance can develop.1 Frequent surveillance is necessary to identify resistance and alter therapy accordingly.

1. van der Hiel, Bernies et al. “Vemurafenib plus cobimetinib in unresectable stage IIIc or stage IV melanoma: response monitoring and resistance prediction with positron emission tomography and tumor characteristics (REPOSIT): study protocol of a phase II, open-label, multicenter study.” BMC cancer vol. 17,1 649. 15 Sep. 2017.

Disclosures:

Jacob M. Bauss, MD1, Jason Puckett, MD2, Chelsea M. Styles, MD3. P2793 - A Case of Malignant Melanoma With Metastases to the Stomach, ACG 2023 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Vancouver, BC, Canada: American College of Gastroenterology.

1Michigan State University College of Human Medicine, Grand Rapids, MI; 2Corewell Health, Byron Center, MI; 3Michigan Pathology Specialists/Corewell Health, Grand Rapids, MI

Introduction: The most common cancers that metastasize to the gastrointestinal (GI) tract are melanoma and breast cancer with the small intestine being the most common site followed by stomach, colon and esophagus. Due to the non-specific symptoms and variability of lesions on endoscopy, diagnosis of metastatic melanoma to the GI tract tends to be delayed. Prompt recognition is important to direct therapy and minimize potential complications.

Case Description/Methods: A 47-year-old male with a past medical history of asthma on 20 mg prednisone daily and metastatic melanoma to the brain, liver, and lungs on vemurafenib and cobimetinib presented to the hospital for two weeks of epigastric pain and melena. A non-contrast CT scan showed new abdominal adenopathy near the gastrohepatic ligament. He was mildly anemic with a hemoglobin of 12.7 g/dL (14-17.5 g/dL). Upper endoscopy revealed a large ulcerated friable mass in the gastric body. Biopsy showed atypical infiltrative cells in the gastric mucosa which were positive for SOX10, HMB-45, tyrosinase, and Melan-A (MART-1) confirming the diagnosis of metastatic melanoma. The patient was placed on twice daily 40 mg pantoprazole and continued on kinase inhibitor therapy with resolution of the melena and improvement in abdominal pain. He was discharged one day following the procedure with close follow-up by the gastroenterology and oncology team.

Discussion: Metastatic melanoma to the stomach is rare with the diagnosis being delayed due to non-specific symptoms. Prognosis is poor with an average life expectancy of 6 months. Endoscopic appearance of gastric melanoma varies greatly among cases necessitating the need for biopsy to confirm the diagnosis via histological identification and immunohistochemical staining. Differentiation of primary GI melanoma versus metastatic melanoma is also important to guide therapy and can be delineated by patient history and genetic markers. Dual kinase inhibitor therapy has shown improved progression-free survival and overall survival when used for unresectable metastatic melanoma, however, treatment resistance can develop.1 Frequent surveillance is necessary to identify resistance and alter therapy accordingly.

1. van der Hiel, Bernies et al. “Vemurafenib plus cobimetinib in unresectable stage IIIc or stage IV melanoma: response monitoring and resistance prediction with positron emission tomography and tumor characteristics (REPOSIT): study protocol of a phase II, open-label, multicenter study.” BMC cancer vol. 17,1 649. 15 Sep. 2017.

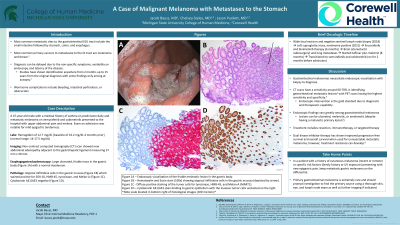

Figure: Figure 1A – Endoscopic visualization of the friable melanotic lesion in the gastric body.

Figure 1B – Hematoxylin and Eosin stain (100x) showing atypical infiltrative cells in the gastric mucosa (depicted by arrow).

Figure 1C - Diffuse positive staining of the tumor cells for tyrosinase, HMB-45, and Melan-A (MART-1).

Figure 1D – Cytokeratin AE1/AE3 stain binding to gastric epithelium with the invasive tumor cells unstained on the right.

*Note: scale located in the bottom right of histological images (100 microns)*

Figure 1B – Hematoxylin and Eosin stain (100x) showing atypical infiltrative cells in the gastric mucosa (depicted by arrow).

Figure 1C - Diffuse positive staining of the tumor cells for tyrosinase, HMB-45, and Melan-A (MART-1).

Figure 1D – Cytokeratin AE1/AE3 stain binding to gastric epithelium with the invasive tumor cells unstained on the right.

*Note: scale located in the bottom right of histological images (100 microns)*

Disclosures:

Jacob Bauss indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Jason Puckett indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Chelsea Styles indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Jacob M. Bauss, MD1, Jason Puckett, MD2, Chelsea M. Styles, MD3. P2793 - A Case of Malignant Melanoma With Metastases to the Stomach, ACG 2023 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Vancouver, BC, Canada: American College of Gastroenterology.